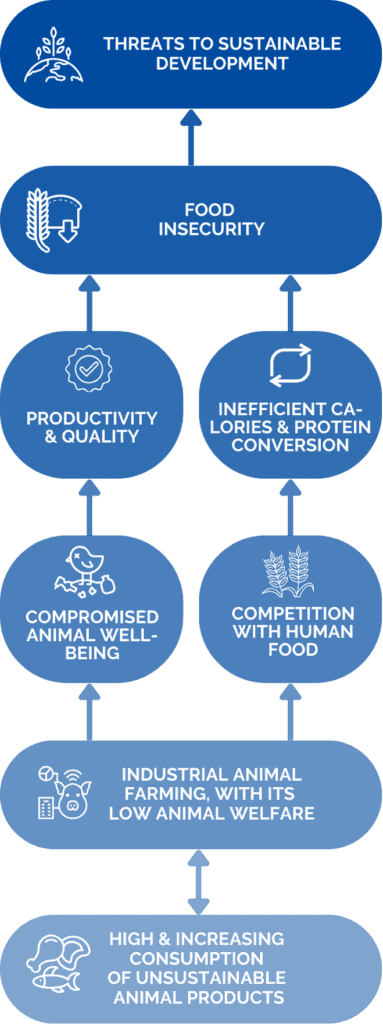

All human beings have the right to adequate food, including all the nutritional elements needed to live a healthy and active life, and the right to be free from hunger. Food security is a public responsibility and a crucial aspect of sustainable development. Its realisation is inextricably linked to health and education outcomes, economic growth, and environmental sustainability. However, the unsustainable production of food can undermine food security in the long run. This is because such food systems can contribute to deforestation, soil degradation, water scarcity, pollution, and greenhouse gas emissions. These negative impacts can ultimately undermine the long-term viability of food production and lead to shortages, price hikes, and reduced access to food, especially for vulnerable populations. Therefore, a shift to sustainable food systems is essential.

SDG 2 aiming to “end hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture by 2030” recognises these interlinkages. In the last decade, however, the number of people suffering from hunger and food insecurity has been on the rise. As many as 828 million people may have suffered from hunger in 2021. It is time to re-evaluate the world’s food systems to provide nutritious food for all while supporting people’s livelihoods and protecting the environment.

The nexus between animal welfare and food security

Good animal welfare practices can contribute to food security by improving the productivity, health, and well-being of farm animals. They can reduce waste and the economic losses associated with disease outbreaks and other production losses, as well as help maintain the long-term sustainability of food systems by reducing the environmental impact of animal production. Animal welfare is indispensable for ensuring food security and nutrition.

Reduced animal protein dependence can enhance food systems efficiency

The industrial production of animal products, particularly livestock, relies heavily on using human-edible food such as cereals as animal feed. Between 36-40 per cent of global crop calories are used as animal feed (see here and here) with even higher proportions in countries with mostly industrial livestock farming (see here and here). Most feed grain, 69%, is used in the highly industrialised pig and poultry sectors.

The use of grain and other human-edible food reduces the global food balance as livestock convert grain inefficiently into meat and milk. According to the FAO, they convert the carbohydrates and protein contained in the grain into a smaller quantity of energy and protein than humans could have gained directly by consuming the grain. For every 100 calories of human-edible cereals fed to animals, only 17-30 calories enter the human food chain, and for every 100 grams of grain protein fed to animals, just 43 grams enter the human food chain as meat or milk. Similarly, 90% of the wild fish used in animal feeds could instead be eaten directly by humans. “Almost a third of the total food value of global crop production is lost by “processing” it through inefficient livestock systems“.

This highly inefficient food system is leading to a net drain on the world’s food supply, causing food insecurity and inequity. According to the IPCC, “aquaculture and livestock dietary components may also compromise crops and forage fish that provide essential nutrients for low-income households increasing nutritional insecurity in regions of sub-Saharan Africa, Asia and Latin America”. In the case of forage fish for aquaculture feed, the food security of coastal communities is put at risk as forage fish is an important source of protein and income.

If food production and consumption continue in their current form, food security will face a double challenge. First, the projected growth of the world’s population to 9.7 billion by 2050 increases the overall demand for food. Second, as people become more numerous and richer, global demand for animal products could potentially increase by 70% until 2050, which will further strain available calories and protein if produced by using human-edible food as animal feed.

To combat food insecurity and malnutrition, available resources need to be used more efficiently. This requires two concurrent changes. First, production needs to shift away from using human-edible food as animal feed. Animals only contribute positively to food production when they convert materials that humans cannot consume into food humans can eat, i.e., if fed on grass (on marginal, non-cropland), byproducts, crop residues, and unavoidable food waste (see here and here). As this would result in a halving of global animal protein production, an equivalent shift in consumption towards more plant-rich diets would be required. The shifts in production and consumption are in line with UNEP’s recommendation to reduce the use of grain production to feed animals and produce more food for direct human consumption. Studies have shown that if the cereals used as animal feed were used for direct human consumption, they could feed an additional 3.5 billion to 4 billion people each year (see here and here).

In the medium- to long-term, alternative proteins, i.e., meat, eggs, dairy, and seafood made from plants and cells without the use of live animals, will likely provide a complementary pathway that could increase the efficiency of food production, while reducing harm to animals. For example, cultivated meat has the potential to be substantially more efficient than traditional meat production methods. Studies suggest that it could use land up to 60-30% more efficiently than poultry and 2,000-4,000% more efficiently than beef.

Better treatment of animals can improve food systems’ quality & productivity

Industrial animal agriculture entails conditions that are detrimental to the welfare of animals. Alternative high-welfare systems can allow for increased productivity without threatening sustainable development. In 2014, the CFS promoted “supporting animal health and welfare (…) to sustainably increase productivity, product quality, and safety”, and in 2016, it further recommended to “improve animal welfare delivering on the five freedoms and related WOAH standards and principles”. Even, the way humans work with, respond to, and interact with animals in food systems can improve or reduce production. For example, in dairy cows and goats, negative interactions with or fear of humans can lead to reduced milk production. In pigs, negative handling can lead to impaired growth and lower reproductive performance. And, in poultry, fear of people can lead to lower egg production as well as poorer quality and slower growth. Additionally, better animal welfare practices can lead to reduced mortality rates.

Higher levels of animal welfare can also result in healthier and safer food for people. Farming of free-range animals that consume fresh forage and have higher activity levels has been shown to provide meat with better nutritional quality than industrially reared animals. For example, pasture-fed beef and free-range chicken have a lower fat content and higher levels of beneficial omega-3 fatty acids compared to grain-fed beef and industrially farmed chicken (see here and here).

Policy Takeaways

It is imperative to transform food systems and supply chains to improve food security and human health and support a more sustainable and humane environment for animals. This will help ensure that food production no longer breaches planetary boundaries.

- By reducing the number of animals industrially farmed, the commercial demand for animal feed can be lowered, making foods like cereals and soy more affordable for human consumption. This, in tandem with improving access to plant-based nutrition, can enhance dietary health and open up significant amounts of land for nature-positive regenerative agriculture, rewilding, or afforestation

- Increasing support for higher animal welfare systems, for example, through agroecological solutions, can improve the quality of food while contributing to the productivity of food systems through healthier animals.

This article has been adapted from our Unveiling the Nexus report in the context of the 2024 High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development as it reviews progress against SDG 2, “Zero Hunger.”