We must learn from the pandemic, or we are doomed to repeat it.

If the pandemic has taught us anything, it is that the worldwide health of humans, domestic animals, wild animals, and the environment are interdependent. Our fates are linked epidemiologically, ecologically, ethically and inextricably across the globe.

We have learnt that our health depends on the health of those around us. Our human right to health includes a right to a healthy environment, and that includes having healthy animals. The pandemic and our environmental crises also teach us that our health depends not only on our local or national environment, but on the health of people and animals across the whole world.

We need to protect animals and our environment across the globe if we have any hope of preventing future pandemics, tackling the triple planetary crisis of climate change, nature and pollution, and achieving our United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

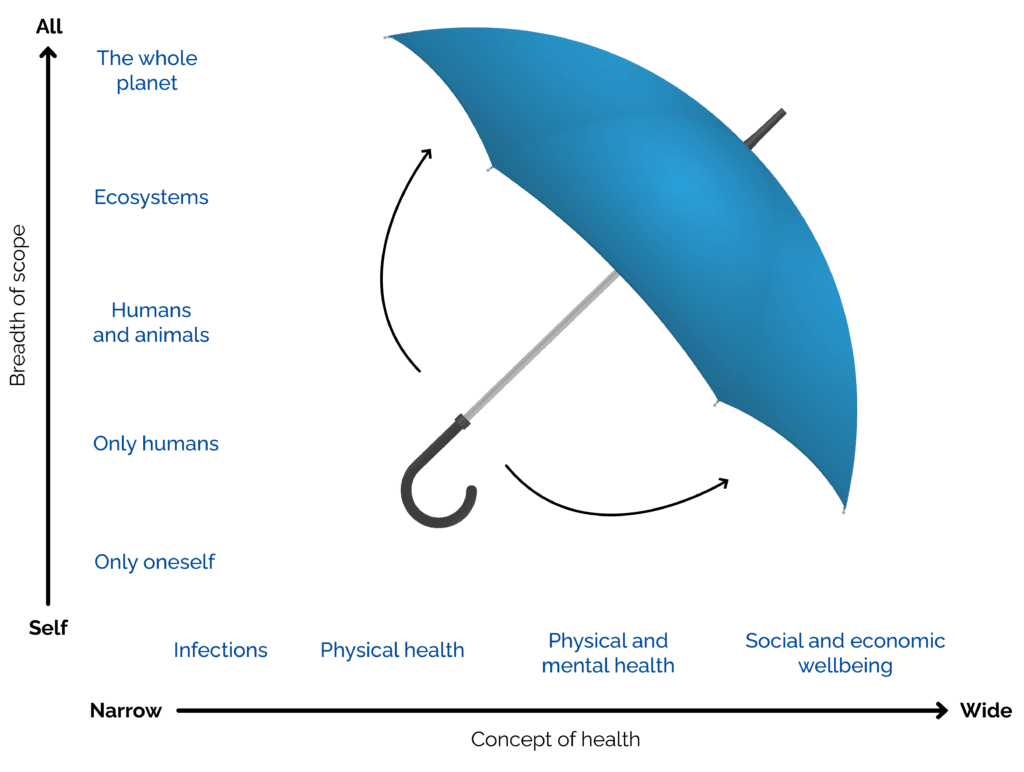

In recognition of this, the FAO, OIE, UNEP and WHO have collectively welcomed a One Health High Level Expert Panel (OHHLEP) definition of One Health as “an integrated, unifying approach that aims to sustainably balance and optimise the health of people, animals and ecosystems.”

This definition contains several elements that together give us a chance to recognise what One Health includes as a truly integrated, unifying, sustainable and optimising approach.

All of health

To be integrated, One Health needs to include all elements of health. (Otherwise, it rather misses the point of having an integrated concept.)

The WHO has long recognised (in its constitution, no less) that health includes physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.

We are less healthy if we are traumatised, inbred, malnourished, stressed, depressed or unable to care for our needs. We should avoid these for humans. Yet we see animals snatched from their familiar niches, starved, confined, transported, overcrowded, mixed or isolated, undiverse, mutilated, and severely stressed.

Poor wellbeing makes us all vulnerable to diseases and less able to fight them off. Alongside other planetary boundaries, we face a pathological boundary when the rise of new diseases outpace animals’ and humans’ collective ability to adapt. Then we risk a point of no return.

So we must look to tackle zoonoses and AMR, and also look deeper at the ways in which we keep and use animals, how we affect their habitats, their food, their groups and their behaviour. We must look at how we design our food systems, research, policies and socioeconomic pressures.

To protect health, we must foster wellbeing. The Tripartite + UNEP definition says this, and it applies to animals as much as to humans.

One for all

To be unifying and sustainable, One Health needs to include everyone’s wellbeing.

Our bodies’ health depends on the health of each organ. If one part is infected, damaged or over-productive, if one part occupies excessive space or uses excessive nutrients, it can lead to problems for other organs or even bodywide conditions like sepsis, endocrine disease, metabolic toxicity, cachexia, space-occupying lesions or metastases.

On a planet, each individual can affect the whole. One animal or person can be the “case zero” of a global zoonotic pandemic. One person or nation that over-consumes can fuel exploitation, deprivation, disruption or destruction. We are used to describing typhoid Mary, psychopaths and contaminated water systems as unhealthy, and so too are unsustainable behaviour, selfish ideologies and exploitative supply chains.

Conversely, the health of one part can also be a symptom of the whole. A rash can be a sign of bodywide sepsis. Human and animal suffering are a sign of an underlying planetary disease, and help us identify the causes – and the cure.

It helps us see how health is related to unsustainable consumption and exploitation of other humans, animals and the environment. It can help us motivate lifestyle and policy changes to transform our health. The pandemic is the wake-up call to take control of our health and our lives.

All for one

To be optimising, One Health needs to align the objectives of different professionals to work as one medical team with shared clinical objectives.

It needs to mobilise “multiple sectors, disciplines and communities at varying levels of society to work together to foster well-being and tackle threats to health and ecosystems.”

It also needs to mobilise collaboration between IGOs. Like a body, each organ may have its specialist role, but they must recognise the overlap between their mandates, as UNEP has done for health and needs to do for animal welfare, to work together in strong future collaborations with shared goals.

This collaboration must be inclusive and genuine. It must move beyond the isolationism, reductionism, neoliberalism, elitism and anthropocentrism that have given us a pandemic in the midst of biodiversity loss, climate change and pollution. It needs to promote systems and policies that genuinely foster wellbeing for all.

Our international agreements and agencies can reflect the practical and selfless compassion that good human medics, veterinarians and ecologists share. This is the remedy to resuscitate our conscience, rehabilitate our behaviour, revitalise our ideology, heal our scars and keep us all unified and healthy.